That question is worthy of a post in itself, but here is a brief treatment: such has been the argument of many for the past several hundred years, and especially in the latter half of the 19th Century, when so much hope was pinned on Man’s domination of the natural world through science and technology. Setting aside all the idealistic conjectures, one has only to look at the brutal harvest of the 20th century to see the results of that false hope. I know the arguments that still try to weasel around the evidence, and I also know that it is almost a cultural norm simply to look past the poisonous effects of anthropocentrism while continuing to swallow the arguments without question. However, to this simple observer, it seems clear that when Man looks no higher than himself for focus and guidance, he quickly drops to the level of a beast.

Granting, then, that anthropocentrism is a state which one might wish to get clear of, how does one go about that? It seems to me that two things are necessary for this; two “feet” to walk on, so to speak. The first of them grates on the modern ear: worship.

Realizing that I risk losing most “non-religious” readers here, I ask you to hold fast for a bit to hear my explanation of that phrase (also, I’ve got a section for you at the end.) I realize that the popular perception of “worship” is either faceless nonentities bowing and chanting in the murk (think Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom) or overdressed women shaking and dancing in ecstasy while the choir claps and the preacher hollers “Hallelujah!” If you can, set aside both these caricatures, as I have been forced to. You see, I was once outright offended by the concept of worship, and not primarily on aesthetic grounds (though that was part of it – after all, who wanted to be like that?) I was offended by the idea of a god who would require his followers to worship him. I wouldn’t think much of a man who asked to be constantly told how great and powerful he was, so how much less a divine being? Especially one who was supposedly good and loving and all-powerful to boot. What did he need, some sort of ego boost?

I eventually learned that the Judeo-Christian God did not by any means “need” my worship, nor did my worship add anything to His existence, any more than my refusal to worship detracted from it. Reading Christian scholars on the topic, I learned that worship was for my sake, not His. This was hard to ignore, since at the same time in my life I was learning by experience that He was as good and loving as I had always been taught, which didn’t fit with the picture of a self-absorbed egotist. But this new knowledge just moved the question to another level: why was worship good for me? What was it about praising God that was beneficial? Wouldn’t that time be better spent learning good moral principles or apologetics?

Even my rather slow perception eventually discerned two beneficial effects of worship. One was that I was speaking true words. To say, “Come, let us bow down in worship; let us kneel before the Lord our Maker; for He is our God; and we are His people, the sheep of His pasture” is not just pleasant poetry – it is first and foremost true. (In fact, it is several truths.) The older I get, the more I realize how important truth-speaking is. Not only is there a shortage of truth in the world, so that every addition of truth is precious, but we men so often speak untruth that it is worthwhile for us to speak clear and certain truth from time to time just to train our tongues to it.

But it was the second reason that fully reconciled me to proper worship. A man who worships is a man who takes his proper place in creation. He acknowledges who God is, who he is, and (ultimately) who his fellow creatures are. True worship, certainly worship in the Judeo-Christian tradition, does not abase man, but neither does it allow him to “put on airs”. He does not pretend he is God, but neither does he pretend that he is less than he is. By lifting his eyes to a greater Being and by taking that Being’s word about his own nature, man “fits in” to where he was designed to be.

Which brings me back to the question about anthropocentrism. Simply put, anthropocentrism is man focusing on himself where he should be focusing on God. It is man trying to assume a different place in creation than the one which was designed for him – which, ultimately, means that he tries to assume the highest place. Oh, any given man might start out in the name of some greater good, usually an abstraction like “the good of Man”, or “the party”, or “the downtrodden”, but almost inevitably it is the individual ego that ends up enthroned. (If the Judeo-Christian tradition is to be believed, there is a reason for this, but we haven’t time to address that right now.)

This is why I think that one solution to the problem of anthropocentrism is worship: it removes man from the center of his own life and puts God back there. That step alone would strike a major blow against anthropocentrism, though I don’t think it sufficient by itself. Since this post is already overlong, I don’t have time to unpack what I mean by “worship”, in the sense of what true worship is, and how it is done. (That will have to wait for another post.) But I do want to take time to address the concerns of those who “aren’t religious” – how do they connect with this?

I’ll set aside for now the questions I have for anyone who claims to not be “religious” (though you can expect a post on the topic), and offer the following suggestion: anything that takes you out of yourself is a move in the right direction. The best sentiment I can identify is something that isn’t commonly found in our world – awe. (One would not expect awe to be commonplace in an anthropocentric culture.) Whether it’s awe at a well-composed symphony, or awe at a natural wonder, or awe at the presence of a loved one in our life, or whatever – the root of awe is acknowledgement of some Great Thing that is other than yourself. To acknowledge that is to start driving a wedge into the hard, egotistical shell of anthropocentrism. The danger is that it is a sentiment, an emotion, and as such runs the risk of being turned inward into a self-absorbed introspection (“Wow! That was something – let’s see if I can get that feeling back again!”) But one has to start somewhere.

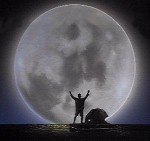

I’ll leave my non-religious readers with one last observation from a surprising source. One of the first (if not the first) Tom Hanks / Meg Ryan movie was a quirky film called Joe vs. The Volcano (details at http://www.mindspring.com/~waponi/). It has a goofy storyline that centers around a loser named Joe who gets roped into a suicide mission and has to deal with Ryan (who plays many roles) along the way. At one point he and the Ryan character get shipwrecked and are floating on a makeshift raft. They are out of sight of land, running out of supplies, and almost certain to die a miserable death, particularly since Joe keeps sacrificing his water to keep the unconscious girl alive. He’s beginning to grasp the insignificance and futility of his life, and is facing the near-certainty that it is going to end soon. In the midst of this he gets to watch the full moon rise out of the still sea and is transfixed by its glory. He stretches out his arms and utters a heartfelt prayer: Dear God, whose name I do not know... thank you for my life. I forgot... how big... thank you. Thank you for my life. Unfortunately, from that poetic high point the movie descends back into goofiness, but that moment alone almost makes the rest of it endurable. That is awe at work, and Hanks is able to pull it off without cynicism or maudlin sentimentality. If you aren’t “religious” but wish to see the truth – reality as it really is – then be ready for those moments – and hope you don’t have to end up floating on a raft to find them.